Fascism and Islam

by Enrico Galoppini

If we have satisfied ourselves with the preconceived schemes influenced by the dichotomies arisen after World War II up to the value of dogma – right / left, racism / anti-racism, colonialism / third world etc. – we would become really tired of making reason for a complex relationship between light and shadow, often contradictory, sometimes enthusiastic and sincere, whichmain characters and situations, that have animated a climate for which, in hindsight, was coined by the historians (perhaps more interested in providing useful material to the news of the Middle East than to the service of Truth) the ungenerous expression of “pro-Arab fascism”.

If we have satisfied ourselves with the preconceived schemes influenced by the dichotomies arisen after World War II up to the value of dogma – right / left, racism / anti-racism, colonialism / third world etc. – we would become really tired of making reason for a complex relationship between light and shadow, often contradictory, sometimes enthusiastic and sincere, whichmain characters and situations, that have animated a climate for which, in hindsight, was coined by the historians (perhaps more interested in providing useful material to the news of the Middle East than to the service of Truth) the ungenerous expression of “pro-Arab fascism”.

Undoubtedly, both the fascist part and that of the Arab-Muslim – to consider them in their complexity and so as not to reduce to the monolithic blocks – were pursuing objectives different in their core, but it is on the path to achieving them that they found themselves in the company along some stretches of the road.

If the disappointment generated by the dictates of the Versailles Peace Conference (19 January-28 June 1919) hegemonized by the United States, Britain and France – that for Italy had translated in the setback of the “mutilated victory” and for the Arab-Islamic world sanctioned the betrayal of the aspirations to independence in the name of Arabism and Islam – had already created the first ground for the encounter between two emerging realities, until the Twenties the foreign policy of Fascism was extremely conservative, but since the early years of the next decade, and especially after the Ethiopian war of 1935-36 (presented to the Muslims as a ransom from the harassment perpetrated against them by the Negus) that that Mediterranean strategy becomes openly pro-Islamic and therefore anti-French and anti-English and adopted with increasing boldness (not to forget that at that time both the Maghreb and Mashreq used to be Arabic, in different ways, under the Anglo-French control of): Arabic studies and Islamic studies acquire a greater boost, the efforts to penetrate the cultural and ideological fields intensify (the Fiera del Levante [Levant Trade Show], in 1930, the Conference of Asian students in Rome in 1933 and 1934, the Italian-Arabic bilingual publications such as Italia Musulmana [Muslim Italy], Mondo Arabo [Arab World], and L’Avvenire Arabo [the Arabic Future], Arabic-language broadcasts on the Radio Bari since 1934) and the spread of the Arab movements and organizations, especially of youth, among which we can mention the Young Egypt Party (Hizb Misr al-Fata) of Ahmad Husayn and the Lebanese Phalanges (al-Kata’ib al-Lubnâniyya) of Pierre Jumayyil among the first, the Green Shirts (al-Qumsân al-Khadrâ’) and the Blue Shirts (al-Qumsân az-Zarqâ’), both Egyptian, and various scout associations (al-Jawwâla) among the latter, looking, perhaps confusingly, at fascism as a model.

In other cases, however, the inspiration was made up of the National Socialism: we can mention the Syrian Social Nationalist Party (al-Hizb al-Qawmî as-Sûrî al-Ijtimâ’î) of Antûn Sa‘âda, the Iron Shirts (al-Qumsân al-Hadîdiyya) in Damascus and Aleppo, the Iraqi al-Futuwwa, the ethics of which originated from that of the knightly orders of the Islamic Middle Ages. But it is with the circles of the courts of the then independent state entities (often only formally) and not with minority and extremist factions that Fascism, realistically, prefers to weave relationships that ina special mode on the commercial level determine theremarkable positions: Yemen of Imâm Yahya is an Italian protectorate in fact (the Treaty of friendship and economic relations of 1926 was renewed in 1937) and good relations became established both with King Fu’âd of Egypt and with the ruler of Iraq Faysal ibn Husayn; while as further proof of the importance of the Italian health and scientific-technical contributions in the Arab world it is enough to recall the permanent medical mission at the Imâm’s of Yemen, the Italian Hospital in Amman, the clinic in Jeddah and the aviation assistance provided to Ibn Sa’ûd during all Thirties.

In the end of the decade, and then during the war (when the Allies impose blackmail and pressure on all of these excellent relations), the pro-Islamism of the Mussolini regime, until then marked by a good dose of pragmatism, becomes, as it were, ideological (fascism as “Islam of the twentieth century” is one of the slogans coined in this climate), but these are only sporadic cases (e.g. the failed Iraqi revolution of Rashîd ‘Âlî al-Ghaylânî and of the officers of the Golden Square supported by the Axis in April-May 1941), and in any case with little conviction, that Fascism and some sectors of the Arab-Muslim world eager to break free from the French-English control fail to take action of some importance. Among the prominent Arab interlocutors who privileged the alliance (more pragmatic than ideological) between Fascism and Islam – ill putting among the rest their hopes in an equally clear rejection of the Zionist entity that was slowly but surely establishing itself in Palestine –we can mention first of all the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Hajj Amîn al-Husaynî (1893-1974), a proponent of the Arab-Islamic planning – and not strictly national – of the liberation struggle of the Dar al-Islam from foreign interference, the Emir Druze Shakîb Arslân (1869-1946), one of the leading exponents of the current reform of the Salafiyya that in Geneva ran La Nation Arabe, Muhammad Iqbâl (1877-1938), the spiritual father of Pakistan, who had words of praise for the opening towards Asia sealed by Duce with the speech of March 18, 1934 on the expansion of Italy in the East Pacific.

In the end of the decade, and then during the war (when the Allies impose blackmail and pressure on all of these excellent relations), the pro-Islamism of the Mussolini regime, until then marked by a good dose of pragmatism, becomes, as it were, ideological (fascism as “Islam of the twentieth century” is one of the slogans coined in this climate), but these are only sporadic cases (e.g. the failed Iraqi revolution of Rashîd ‘Âlî al-Ghaylânî and of the officers of the Golden Square supported by the Axis in April-May 1941), and in any case with little conviction, that Fascism and some sectors of the Arab-Muslim world eager to break free from the French-English control fail to take action of some importance. Among the prominent Arab interlocutors who privileged the alliance (more pragmatic than ideological) between Fascism and Islam – ill putting among the rest their hopes in an equally clear rejection of the Zionist entity that was slowly but surely establishing itself in Palestine –we can mention first of all the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Hajj Amîn al-Husaynî (1893-1974), a proponent of the Arab-Islamic planning – and not strictly national – of the liberation struggle of the Dar al-Islam from foreign interference, the Emir Druze Shakîb Arslân (1869-1946), one of the leading exponents of the current reform of the Salafiyya that in Geneva ran La Nation Arabe, Muhammad Iqbâl (1877-1938), the spiritual father of Pakistan, who had words of praise for the opening towards Asia sealed by Duce with the speech of March 18, 1934 on the expansion of Italy in the East Pacific.

It would be a mistake – abstracting from the historical context of this story – to pin down as anti-Semitism the glue of these vague mutual friendship: it has never been precisely pertinent neither to Arabs nor to Muslims, and for Fascism it was a tardy trend, minor and instrumental fruit of the political alliance with Hitler’s Germany; while it is often silenced the hostile attitude that already since 1936 the main Jewish organizations demonstrated against fascist Italy. And it is also to be remembered that the Jewish communities traditionally residingin Palestine coexisted peacefully from time immemorial with both the Arab Muslim majority and with Arab Christian minority.

Whether it was a wavering and contradictory pro-Islamism it is also demonstrated by the “Islamic politics” pursued by Fascism in Libya, where the nodes of what often appears to be a strategy aimed mostly to counter the Franco-British hegemony in the Mediterranean and manage the Muslim populations of the colonies (Libya, Eritrea, Dodecanese, then Ethiopia and Albania finally) come home to roost. Here Islam is indeed encouraged – to the point of making life difficult for those who saw an opportunity for a new evangelization of North Africa – with initiatives aimed at supporting local religious life (restoration and construction of mosques and Koranic schools, assistance for the pilgrims to Mecca, the opening of the School of Islamic Culture in Tripoli), but it is mainly an instrument of order, gradually forced to the private sphere in compliance with the “render unto Caesar” that just fits the intimate essence of Islam. Even Fascism then – among which constituent elements are aversion to many of the principles of the Enlightenment and to some of “progressivism” – in colony eventually had flatten out in the reproduction of the rhetoric of progress (of “development” we would say today) setting up the version in black shirt of the “civilizing mission”, including the essential baggage of “good intentions” inherent in any oversea business. The journey of Mussolini to Libya in March 1937 – a “reward” for people who with the contingents of askari had given a fundamental contribution to the conquest of the Empire – which culminated with delivery to the Duce of the “Sword of Islam”, actually opened a new and massive phase of settlement of settlers on the Fourth Italian bank (the “Twenty thousand” of 1938), an event that could not but worry of the advocates of ethnic and cultural integrity of the Arab Homeland (al-Watan al ‘Arabî), primarily the contiguous Tunisian nationalists of Neo-Dustûr Habîb Bourguîba, occasionally drawing close to Fascism.

Whether it was a wavering and contradictory pro-Islamism it is also demonstrated by the “Islamic politics” pursued by Fascism in Libya, where the nodes of what often appears to be a strategy aimed mostly to counter the Franco-British hegemony in the Mediterranean and manage the Muslim populations of the colonies (Libya, Eritrea, Dodecanese, then Ethiopia and Albania finally) come home to roost. Here Islam is indeed encouraged – to the point of making life difficult for those who saw an opportunity for a new evangelization of North Africa – with initiatives aimed at supporting local religious life (restoration and construction of mosques and Koranic schools, assistance for the pilgrims to Mecca, the opening of the School of Islamic Culture in Tripoli), but it is mainly an instrument of order, gradually forced to the private sphere in compliance with the “render unto Caesar” that just fits the intimate essence of Islam. Even Fascism then – among which constituent elements are aversion to many of the principles of the Enlightenment and to some of “progressivism” – in colony eventually had flatten out in the reproduction of the rhetoric of progress (of “development” we would say today) setting up the version in black shirt of the “civilizing mission”, including the essential baggage of “good intentions” inherent in any oversea business. The journey of Mussolini to Libya in March 1937 – a “reward” for people who with the contingents of askari had given a fundamental contribution to the conquest of the Empire – which culminated with delivery to the Duce of the “Sword of Islam”, actually opened a new and massive phase of settlement of settlers on the Fourth Italian bank (the “Twenty thousand” of 1938), an event that could not but worry of the advocates of ethnic and cultural integrity of the Arab Homeland (al-Watan al ‘Arabî), primarily the contiguous Tunisian nationalists of Neo-Dustûr Habîb Bourguîba, occasionally drawing close to Fascism.

An overall judgment must therefore reveal that the action of the pro-Muslim Fascism (or “pro-Arab”, when the item “race” began to weigh more in the later rapprochement with Germany) resulted mainly in propaganda and disturbance activities (even the Palestinian uprising of 1937-39 was not backed up with particular enthusiasm) aimed to grab the sympathy of the Muslim populations of the Mediterranean, the center of gravity of the “renewed Empire of Rome”, who however – disappointed by those who had withdrawn all the promises made at their time – saw in these proclamations the possibility to succeed in completing the anti-colonial liberation struggle, later continued after World War II by the champions of pan-Arabism (Jamâl ‘abd en-Nâsir and his followers), accused from time to time – not surprisingly – by the propaganda of their opponents in “fascism”, and even held up as a new “Hitler”.

However, reading many writings published in Italy in between the two World Wars in the climate of the search for a “consultation with Islam”, there can be seen how much the tones of the debate (of course it is good that itexists at all) on today’s Islamic presence in Italy and fears instilled by those who have interest to wave at every turn with the specter of “Islamic fundamentalism”, arefar fromthe setting of the delicate and fundamental question of the relations between Italy (and then Europe) and Islam, between the West and the East.

***

For more information:

Enrico Galoppini, Il Fascismo e l’Islam {Fascism and Islam}, Edizioni all’Insegna del Veltro, Parma 2001.

Interview with Stefano Fabei (by Giovanna Canzano).

Stefano Fabei, La politica maghrebina del Terzo Reich {Maghreb Policy of the Third Reich}, Ed. All’Insegna del Veltro, Parma 1988.

Stefano Fabei, Guerra santa nel Golfo {Holy War in the Gulf}, Ed. Ed. all’Insegna del Veltro, Parma 1990 [History of the Iraqi anti-British insurecction, 1941].

Stefano Fabei, Fascismi e decolonizzazione {Fascism and Decolonization}, “Studies Piacentini”, 16, 1994, pp. 81-109.

Stefano Fabei, Gli arabi nell’esercito italiano {Arabs in the Italian army}, “Studi Piacentini”, 30, 2001, pp. 227-243.

Stefano Fabei, Il Reich e l’Afghanistan {The Reich and Afghanistan}, Ed. All’Insegna del Veltro, Parma 2002.

Stefano Fabei, Il fascio, la svastica e la mezzaluna {The Fasces, the Swastika and the Crescent}, Mursia, Milan 2002.

Stefano Fabei, Una vita per la Palestina. Storia di Hajj Amin al-Husayni, Gran mufti di Gerusalemme {A life for Palestine. History of Hajj Amin al-Husayni, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem}, Mursia, Milan 2003.

Stefano Fabei, Mussolini e la Resistenza palestinese {Mussolini and the Palestinian Resistance}, Mursia, Milan 2005.

Articolo Precedente

Articolo Precedente Articolo Successivo

Articolo Successivo The mysterious object. The image of Islam in Italy in between the two World Wars

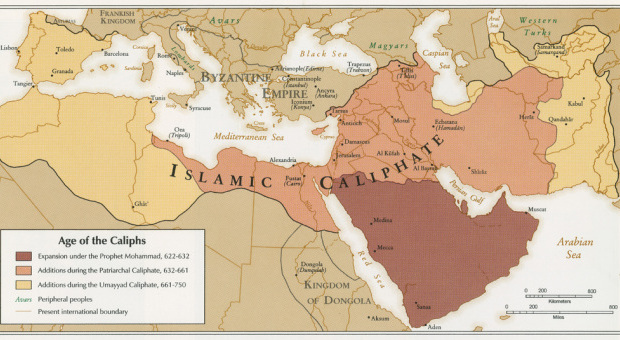

The mysterious object. The image of Islam in Italy in between the two World Wars  Considerations over the institution of the Caliphate and the “Justice” in Islam

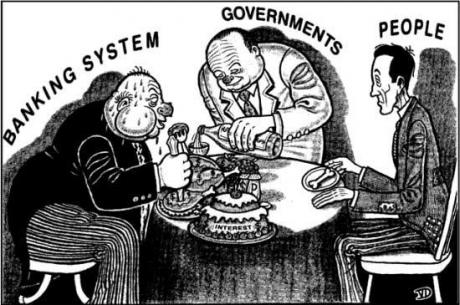

Considerations over the institution of the Caliphate and the “Justice” in Islam  Economic globalization: “Swindlers of the world, unite!”

Economic globalization: “Swindlers of the world, unite!”  ISIS: the Vice Squad has arrived to Mosul!

ISIS: the Vice Squad has arrived to Mosul!  Enrica Perucchietti & Gianluca Marletta, The Factory of Manipulation, Arianna Publ., Bologna 2014

Enrica Perucchietti & Gianluca Marletta, The Factory of Manipulation, Arianna Publ., Bologna 2014  America: but which … “Country of Immigrants”!

America: but which … “Country of Immigrants”!  Is “free Libya” an appendage of ISIS?

Is “free Libya” an appendage of ISIS?  From Bin Laden to the Caliph: the final war against Islam (to knock out Eurasia)

From Bin Laden to the Caliph: the final war against Islam (to knock out Eurasia)

Grazie. A wonderful clear if not complex recount of facts. Indeed a portal to much ignored still.

Hello,

How can i get the book

Fascism and Islam

Enrico Galoppini

Regards